In The Light

Summary

In The Light is a first-person adventure game set in Northern California’s forests. Players are guided through a personal experience of dealing with life’s later waves of grief while exploring a forgotten home and discovering audio cassettes that unlock new memories. This experimental project utilizes homemade audio cut from my own home videos to create an intimate 5-to-10 minute experience about coming to terms with losing a family member.

This was my MFA thesis, built over 9 months as a solo developer in Unreal Engine 5. The game explores how digital spaces can serve as containers for physical memories and emotional processing. Further, it explores how memory can be warped by the experience of grieving.

Details

Design Goals

The primary goal of In The Light was to explore how grief and time change our memories of our departed loved ones. By incorporating actual audio cut from my family’s personal home videos into the game’s soundscape, I aimed to create a deeply personal experience that blurred the line between a space to play and a space to reflect.

I additionally sought to:

- Create an intimate, emotionally resonant experience

- Learn to design environmental storytelling that revealed narrative through exploration

- Utilize lighting, post-processing effects, and game mechanics to convey emotional states and narrative beats

- Learn the full process of making a game, from ideation to publication

Technical Implementation

Engine Selection

One of the key aspects of building In The Light was the engine: Unreal Engine 5. I selected UE5 in part because I wanted to explore the engine’s toolsets and make use of its powerful lighting capabilities and expansive material editor to create my game’s atmospheric environments. Additionally, the engine’s level design tools were a boon to iterative game design, allowing me to continually sculpt, build, and re-build the world until it accurately captured the game’s dreamy, unreal rendition of the Lassen National Forest area. Using UE5 also meant I could make use of tools like the Brushify plugin to enhance my vision for the game’s world.

The last reason for choosing UE5 was blueprints: I knew I was not a strong programmer early on in the game’s ideation stage. Blueprints were a fantastic way for me to accessibly learn game programming logic and patterns on my own terms, and were easy enough to edit that I could quickly iterate on my mechanical design concepts.

Core Technical Systems

- Custom Blueprint systems for item interaction, dialogue, portals, and audio playback:

I wanted players to be able to interact with the world and dialogue without requiring too many different keybinds. I solved this issue using Blueprint interfaces to handle the cross-talk between blueprints and was able to make sure that, in situations like overlap checks crossing with interactables and portals at the same time, certain types of interaction were given priority over others. Additionally, I was able to use blueprints to streamline interactions, like auto-opening doors, so that players could easily navigate without having to remember too many buttons to press in a game that was too short to memorize a variety of keybinds.

- Dynamic Lumen-based lighting setups and post-processing materials that respond to player progression via level and event triggers:

I knew that I wanted a core focus of the game to be its art and atmosphere. Unreal’s post-processing system immediately solved a number of problems for me: it’s both powerful and flexible, and I was able to use it to dynamically swap post-processing effects in realtime without it effecting performance. Lumen GI also allowed me to create dramatic, powerful lighting setups, and gave me the freedom to explore staging lighting in the world without having to re-bake lighting at regular intervals. This sped up my iteration process for designing the game’s atmosphere a considerable amount.

- Audio mixing and customization using Unreal’s Audio Mixer system:

Since audio was crucial to how my game helped the player navigate the space and the feel of the world itself, I needed a solution for designing that soundspace. I considered tools like FMOD, but I felt Unreal’s built in audio systems (sound cues, sound classes, and mixes) were already very strong and easy to use. They were a great, built-in solution that allowed me to play sound triggers, create custom mixes of my audio samples, and fade in/out audio as needed depending on the player’s location.

- Environmental design built with Unreal’s terrain tools and Brushify:

One of my learning focuses was on building a realistically scaled environment: I wanted the world to feel like an actual place that the player could walk around in in real life. The terrain tool in Unreal was flexible enough through tools like components that I could play around with a variety of terrain layouts and come to understand scaling in level design. Additional tooling like the Brushify plugin, runtime virtual textures for placing objects like roads, and Unreal’s foliage system were also incredibly helpful. They really enabled me to build out the forested space and have it feel like an old valley nestled by trees.

Additional UE Tools

- Unreal UI Widgets: Since my game needed to tell a story with text, I learned how to build a styled UI with UMG—and even learned to animate it!

- Unreal’s profiling tools: My game made use of a number of post-process effects and Lumen, so I had to learn how to use, read, and respond to information from tools like Unreal’s view modes, GPU profiling, and Insights.

Development Pipeline

- Reaper and DaVinci Resolve for audio extraction/processing

- Blender for building prototype assets

- Diversion for version control

Development Timeline

The project was developed over 9 months as a largely solo effort, encompassing all aspects of game development including production, level design, programming, audio design, and narrative structure. The compressed timeline required careful scope management to execute the project’s vision while maintaining its emotional integrity.

Ideation

My MFA thesis process was broken into 3 quarters of work, from Winter 2024 to Fall 2024, with a summer break between two phases. The first quarter was incubation studio, where we primarily engaged with ideating our thesis projects. This lasted from early January to late March of 2024. The quarter provided guided structure for ideating and pitching thesis concepts. I decided early on to handle classwork as devlogs, which can be read here. Though I didn’t maintain writing devlogs after the quarter was over, they served as a useful archive for reflection and critique.

I came into the class with a notion of what I wanted to explore. I’d always wanted to make a piece of art that commemorated my father. I explored a few key ideas related to this concept as I worked during the quarter: objects as vessels for memories, the experience of dealing with grief later in life, and the effect time and grief has on memories and nostalgia. I also set a few early narrative ideas in stone at this point: the game would take place in a forest reminiscent of Lassen National Forest, as it was where my family vacationed when I was young. Forests are also naturally isolating, and I felt this would help with building a cold, unnatural atmosphere. Additionally, I wanted the player to discover the game narrative through item pickups—I was very interested in spatial design, and how levels can communicate histories without directly telling the player a story.

I had to do quite a bit of research into Lassen’s native flora to make sure that the game’s level accurately captured Northern California’s forests, and also built reference boards for housing architecture trends in nearby areas. I also spent a bit of time in UE5 testing out its lighting and level design tools to evaluate its fit for my project. Below are some images from that phase that were integral to the eventual game design document I wrote.

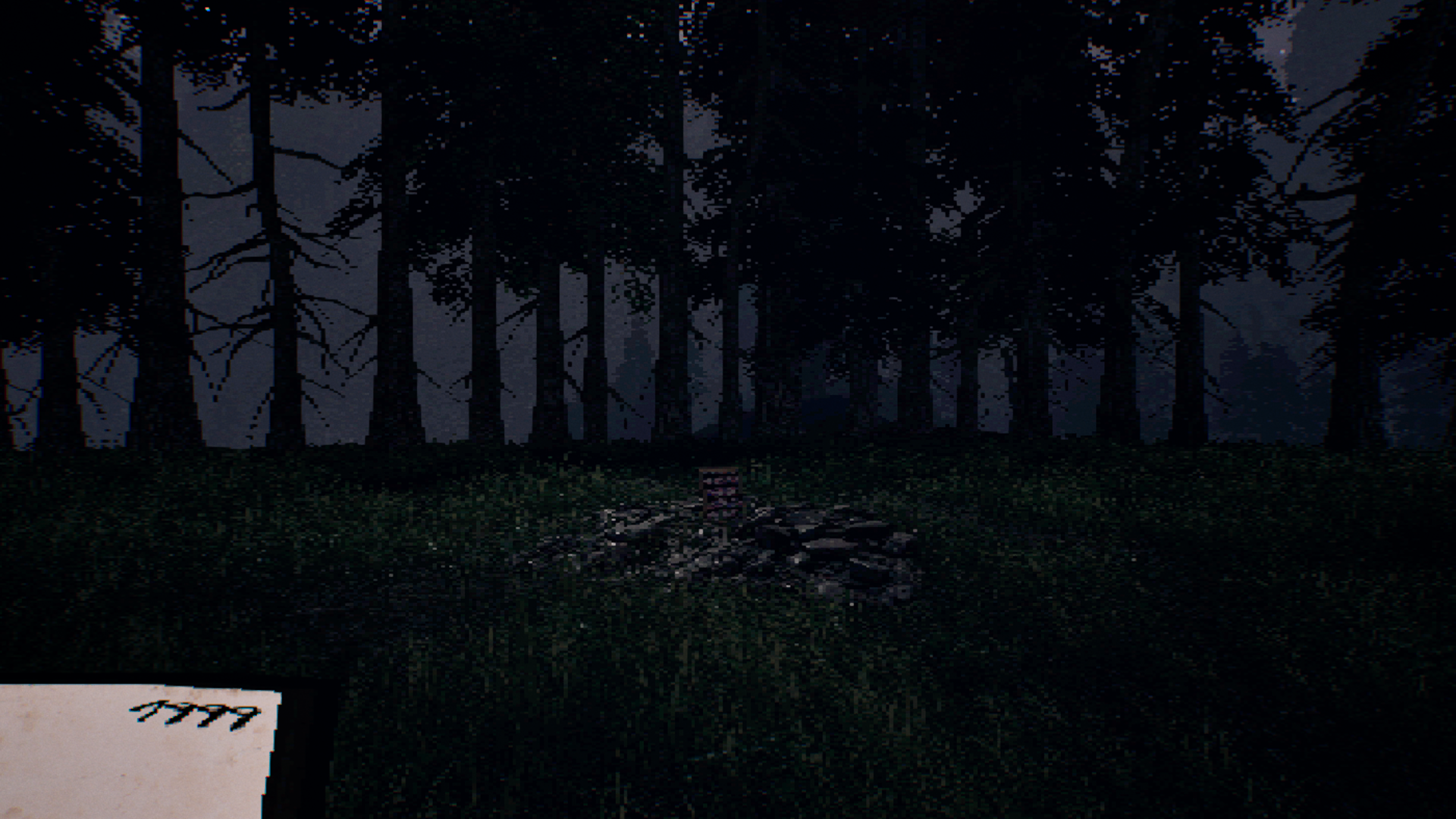

This is a screenshot from the first ever build I made for ITL. I was mostly trying to learn how to use the lighting tools and object controls at this point. I found the mood lighting pretty evocative and learned I love designing game lighting through making this project.

This is a screenshot from the first ever build I made for ITL. I was mostly trying to learn how to use the lighting tools and object controls at this point. I found the mood lighting pretty evocative and learned I love designing game lighting through making this project. This was the first concept piece I made for the game, which I made around the time I began to write the GDD in mid-February. I really wanted to capture the idea of being lost in a forest surrounded by the dilapidated remains of the people who once lived there.

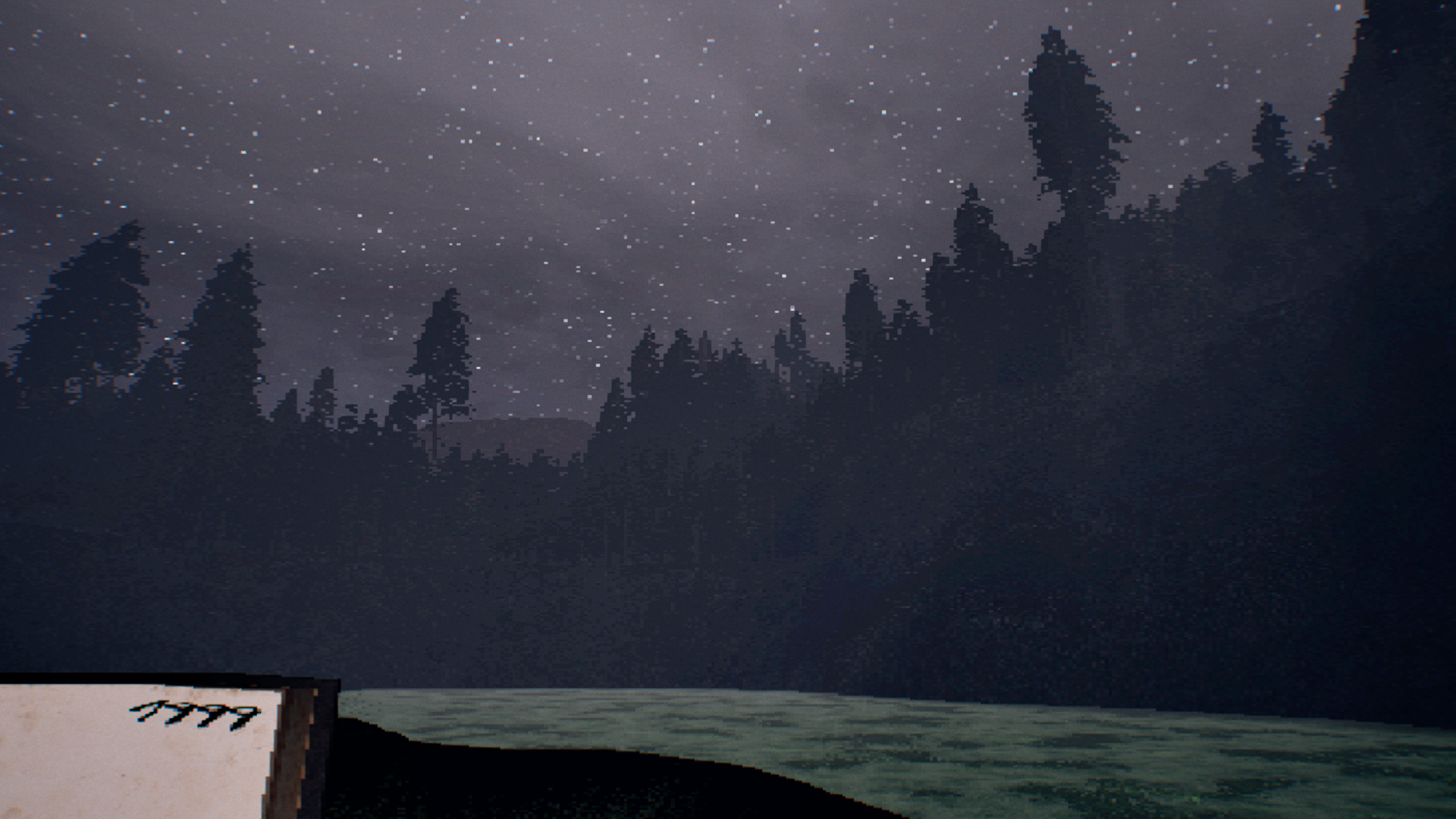

This was the first concept piece I made for the game, which I made around the time I began to write the GDD in mid-February. I really wanted to capture the idea of being lost in a forest surrounded by the dilapidated remains of the people who once lived there.Prototyping

The prototyping phase was the longest phase, and started around halfway through incubation studio—once I had enough ideas to gesture at that I could start working in-engine around early February. This was also when I picked my thesis advisors. I chose Allen Turner as my chair, and Jes Klass and Richard Wetzel as secondary advisors. Their combined expertise in Unreal, level design, narrative design, and UI/UX was essential to the project’s development.

Prototyping’s main phase took place over Spring quarter of 2024, from late March to early June. This phase voluntarily extended into summer. Early on, I focused on trying to set up strong time management for myself, as I knew this was my first time really approaching a project of this scale, and I didn’t want it to get out of hand.

The bulk of Spring quarter was spent defining the core mechanic, which I’d only vaguely described by this point. I was inspired by Tyler Glaiel’s 2012 puzzle game Closure, and had an idea about using light to “reveal” unseen, liminal spaces in the game world. The key element was the notion that spaces and memory could be hidden away, and required effort to find them again. After researching gameplay mechanics, I changed the concept into using portals as a system for traversal and storytelling.

This captured what I was looking for, as portals are a transitional element that can open gateways to novel locations, and could represent traveling between different times, reality, and memory. I sat down and played Portal for research, built gameplay paper prototypes, and started drawing some ideas for the game’s central level. I also began really learning to program with blueprints for the first time. I built several small prototypes as I figured out tools like line traces, material parameters, and controlling object responses to collisions using custom channels and gameplay tags. At this point, my technical approach was based on using render targets to capture a live image from secondary cameras that was then drawn to a material.

Around August, I’d built a greybox of the central house level, and I had prototype portals the player could look at and walk through. By this version, I’d made the decision that players could only open portals in designated doorways. This was for two reasons: one was sheer complexity. I definitely did not have strong enough math skills at the time to be able to figure out portals being spawnable anywhere on a wall. It was also too Portal-y, and didn’t really cohere with my design goals to let players freely portal wherever. Restricting the interaction to doorways gave the portals a stronger connection to being literal liminal doors, and also gave me more freedom to learn how to design puzzles with stricter rules.

I also created the interactable item system—the idea developed into players wandering around an abandoned house and collecting cassettes that would play the audio from my family’s tapes. Collecting cassettes would unlock the next stage of the puzzle they were on, until they eventually discovered some kind of hidden truth. Much later into the game’s development, I made a small change so that picking up cassettes would trigger actual dialogue boxes instead of audio. Regardless, the bones of the item system and the cassettes stayed through the rest of development.

Most of my time prototyping was spent learning programming and Unreal’s tools, and I’d deprioritized narrative and visual work to focus on gameplay systems. At this time, I knew I’d need a custom asset for the house my game was going to take place in. One option was using pre-made assets and modifying materials to make the assets feel close to what I wanted visually. However, doing that would not fully capture the specific design and aesthetic I had in mind, and I couldn’t solve the issue by making my own custom asset, as it would eat up time better spent elsewhere. The other option was finding an artist to create the model for me.

I went with the latter option, and worked with one of my thesis advisors to bring on fellow masters students Becca Benson and Shikha Patel to help with my modeling needs. The both of them were incredibly helpful for the rest of the project: they gave me feedback on art ideas, pushed me to think about new possibilities for my thesis, and, of course, assisted me in getting the final house model made.

This is a screenshot from my first time trying to build portals in UE5. I was very proud of getting the visual functionality to work.

This is a screenshot from my first time trying to build portals in UE5. I was very proud of getting the visual functionality to work. This is from a later point in prototyping. I’d done a lot of scrappy renditions of box-shaped houses. Late in the summer, I’d drawn enough concept maps that I could build a much stronger, fully-envisioned playtest environment for the game’s central house.

This is from a later point in prototyping. I’d done a lot of scrappy renditions of box-shaped houses. Late in the summer, I’d drawn enough concept maps that I could build a much stronger, fully-envisioned playtest environment for the game’s central house.Playtesting

Playtesting mostly occurred over fall quarter in 2024. By this time, I had the prototype portal system and an early version of the whole level space. I’d also neglected several key areas: I did not have the narrative written, I had no UI, and I did not have much of the game art done. The playtesting phase involved juggling several tasks behind the scenes while presenting the game to others. Most critically, the portal system had persistent bugs involving spatial math and rendering issues, and I had to try to work on narrative and visual elements concurrently.

After initial narrative exploration, I brought a presentation on my game’s concept and aesthetics to a playtesting course my university runs. I showed my concept art and talked over my narrative ideas. Their feedback gave me a stronger idea of how I wanted to approach telling a story about grief and memory. Later, I had my chair hand out a UI-focused build of my game to one of his classes, with a Google Form people could respond to. Despite the clarity these early playtests offered, progress on both narrative and UI stalled halfway through the quarter as the portal system bugs consumed my time.

This was one of the hardest phases as a solo developer, especially within the 10 week quarter timeline. The broken portal system prevented meaningful playtesting; I couldn’t produce new builds past the first few weeks because most of my time was spent debugging instead of adding new content. A lot of ideas got cut, and I realized I’d still managed to overscope despite my production efforts.

This realization came at the worst possible time: my game was scheduled to be shown at the Midwest Game Developer’s Conference as part of DePaul’s booth. A week before the conference, I started building a demo level with atmospheric elements I’d been planning: materials for the house, fog, trees with wind, grass, dynamic indoor and outdoor lighting, and a secondary level space hidden below the landscape the player would teleport to from the house’s doorways. A few days in, I discovered a problem: I’d never tested my portals with more than basic lighting and fog. Due to how they were constructed, using render targets captured in real time without disabling any post-processing or implementing proper cleanup, the framerate collapsed after using them more than just a couple times.

I had only a couple days to fix it without rebuilding the level. I combined multiple solutions: reduced render target resolution, disabled all post-processing within the render targets, cut a number of portal doorways, and created a very brief narrative path players could follow that would end after a few minutes. After a week of building and then frantically fixing, I finally had a buggy but playable build.

Despite the rough build quality, the Midwest GDC showcase was my favorite playtest. Getting to see strangers choose to sit down and play something I’d made at a game show for the first time was magical. I learned so much from my conversations, and the warm response bolstered my confidence.

This phase of work ended at the start of winter break. This gave me about 2 months to recuperate and address the narrative and visual elements of my game I’d left behind while working on the portal system.

Polish

Since thesis defense was supposed to take place in March, I had a deadline of mid-February to turn in my final build and thesis paper so my advisors had time to read and play. I knew that I could achieve a strong final project—I just had to map out the steps and be willing to get rid of anything that did not drive progress forward. That meant prioritizing functional portals, a narrative, the UI, and the custom audio using my family videos.

The portals needed to change. I knew that the render target implementation had performance issues, and it didn’t feel like they were fully capturing the journey between grief stages and time periods just yet. My chair suggested using cubemap textures as an alternative, but the timeline for rendering all necessary cubemaps while building the world was unrealistic.

I searched for alternatives, and came across an Unreal asset that was seamless portals… using post-process transitions. I got it set up in a separate project, inspected how the maker designed the blueprints and materials, and found the spark of inspiration I’d been needing. I adapted their approach in my project, removing the render target system entirely and rebuilding the portals using post-processing materials. This not only fixed the performance issues, but also sparked an idea: I could use post-processing to visualize dealing with grief.

I designed a visual language for the stages of grief. I had a greyscale shader for depression, a blue shader for bargaining, and a bright red shader for anger. Acceptance became a PS2-style shader: it was the aesthetic I grew up with and represented the games I played with my dad. It was both personally meaningful and broadly nostalgic. As players traveled between time periods and collected cassettes left around the house, the post-processing effect would change for each successive portal, visually representing their progression through grief.

Finally having working portals that had a clear connection to my thesis’s themes was freeing. I showed the new system to my partner and my friends, and it removed a massive blocker and enabled me to see what the rest of the game needed to be.

The next step was to finally start digitizing and then editing the content from my family’s old home videos. There were about 12 hours of videos to go through, and I was searching for very specific content: I wanted video and audio of my dad talking to or about me. Since digitizing VHS required playing back the content, it let me multitask and take notes on what could be useful.

As I watched and took notes, I had the realization that my dad only had a presence in my older sister’s videos, and the only person in mine was my mother. I’d watched these videos years ago, and it felt like my own memory had betrayed me. Instead of panicking, I realized that this was exactly the experience I wanted the player to have in the game’s story. It’s a game to my father, about my father, and he could not even be present in a work dedicated to him. I had misremembered his time in my life from my own grief. This absence became the emotional core that would drive the player’s progress through the visual grief stages I’d designed.

I noted down a few moments of him talking from my sister’s videos and a few interesting sounds that I wanted to add to my game’s soundscape. Once digitization was finished, I brought the relevant files into DaVinci Resolve and extracted the audio I needed. The last step was some minor cleanup and editing in Reaper before the files were ready to be used.

Next was finally writing the whole narrative. I left the player character nameless to emphasize immersion and blur the line between player and character. They would arrive at night to a remote forest road, cut off from society in this place out of time. Before them would sit a house on a hillside, lit up and welcoming despite the isolation. No other characters would appear; the game would be entirely about the player’s solitary journey through grief.

I decided to leave the portaling ability unexplained and unacknowledged by the character. Players would gain it after collecting the first cassette tape, with a triggered sound guiding them back to discover the portal action prompt. The portals needed to feel metaphorical—a vivid, abstract representation of moving through memories. The character’s internal dialogue would play out upon each subsequent cassette pickup, progressing through anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I then wrote out the actual dialogue, centering a nameless lost loved one that the main character had once lived with in this abandoned house. I wanted the house to feel like its own character: it had its own connection to the player character, and it guided them through realizing what their loved one left behind and realizing that they needed to move on.

With the narrative framework clear, I began building the final version of the level. I took my greybox house and copied it to a new map, where I used its scale to help sculpt a new, more detailed surrounding landscape. I used a couple Brushify packs to populate the landscape with flora, blending between greens and browns to make the world feel like it was struggling to keep going on. I needed the player to have a clear, signposted path into the house, and used diegetic light posts to highlight the hillside route up.

I added other grounding details: I blocked out the playable space with fences and a river, and added a backyard lake and a secondary hill that was locked off until the end of the game to represent the final ascension to acceptance. Last was building the lighting—I set the game in nighttime, and used dramatic, sparse lighting throughout the house to both signpost doorways and to make the home feel cavernous. I also added a flashlight mechanic for navigation.

Though I completed the primary level layout and lighting by late December, I continued refining the environment throughout January, adding fog, set dressing, and atmospheric details. The final house asset was finished and implemented about a week before the deadline.

In early January, I built the final UI, stylized around a VHS aesthetic that tied to the home video theme. I based the dialogue boxes and all menu elements on VHS label textures.

I also implemented diegetic UI with a journal in the bottom left corner of the screen that displayed the current year as players moved between time periods. Since time period transitions were crucial to my narrative, I needed to display them clearly. This, ironically, turned out to be a perfect use case for render targets. I created a small rendering setup with cameras pointed at book pages displaying ‘1997’ and ‘2007’, then piped those images into the journal asset. A simple conditional switch from the portal blueprint changed which year displayed based on the active time period.

Defense

I scheduled my defense for March 11, 2025 and was the first of my cohort to defend. I sent out Zoom invites to all my close friends and loved ones. The anxiety was unreal, but I could also see the light at the end of the tunnel. I’d sent off the final build and paper to my advisors, and I had to sit with the fact that my work was done. I just had to trust in it.

I’d picked out a nice conference room, which came with a massive floor-to-ceiling screen and a small monitor in the back I could use as a teleprompter. I had to make a brief presentation to talk through that described the process, intent, and result of the work, and then there’d be about an hour of questioning from my advisors. I think I was more scared of the presentation than the questioning—I knew my work did everything it needed to! I just needed to be able to show that.

On the day, I stood in front of that giant screen, took a deep breath, and welcomed everyone to my defense. I absolutely speedtalked through my presentation, nerves eating me alive. Questioning was tougher than I thought it was going to be, and I simply had to stand strong, speak with clarity and composure, and make it clear that every decision I’d made in the game was intentional. And I survived.

I survived, and I passed without revisions.

It is still one of the happiest days of my life. I tried not to cry, but broke down with relief the moment I was given my judgment. I’d made a game about my father, shaped by his absence in my memories, and it existed now as its own memory—proof that he’d been here, that he mattered. Today, I have my MFA. In The Light became both the memorial to my father I needed to make, and an act of empathy for anyone else carrying loss.

Gallery

Reflection

What Went Wrong

Making In The Light was incredibly challenging, and my ambitions became a thorny trap. There were so many little things that I wanted to learn how to do and ideas I wanted to make. One of my original concepts was a much more Dark Souls inspired method of narrative storytelling—I didn’t want to write dialogue at all, and I wanted the player to essentially learn the story through materials left around the house. This went out the window once I started having technical issues and it also just didn’t really fit the emotional goal. I wanted to have multiple level areas! I wanted whole puzzles, traversal mechanics, and I wanted to make a map (Silent Hill 2 Remake came out partway through playtesting and I was obsessed with their maps). Making this game was a brutal lesson in what it really meant to overscope a game.

Portals were an intense way to learn programming gameplay systems. There were a lot of missteps. I jumped into the engine immediately, I didn’t plan or write out psuedocode, and my adjustments to the system happened pretty much on the fly. I was trying really hard to emulate others’ programming as well because I was so unfamiliar with the vast majority of the concepts that went into making portals work. I thought I was taking a measured approach to the game’s development, but I underestimated how much I’d left undocumented or not thought out. I also think I just got stuck on concepts for too long. I tried so hard to make one particular version work, instead of trying to find new solutions.

The playtesting phase in particular was a wash. It’s unfortunate that basically all of my final work went untested, because there were innumerable bugs players came across later on. I just had to take it on the chin and knew that, regardless of bugginess, the core of the game worked.

Lastly, I wanted to make a horror game. Nothing about my thesis is a horror game. This was a natural shift that happened over time, and the work is more than likely better for it, but I kept trying to find ways to bring it back to horror instead of accepting what it was becoming. I think this was a major blocker for building the narrative, because the game that I was building was not even close to the tense atmosphere I was envisioning.

What Went Right

The game resonated with people. Some of my favorite memories came from the graduate thesis showcase event, which I thankfully got to participate in after defending. Partway through, one of my advisors sought me out and showed me a stranger, who who apparently had something to ask. They looked at me and just said, “Did your dad die?” It was absurd and made me laugh, and of course I said yes. Another person found me just to tell me that my game really impacted them and made them cry. Somebody else even asked me if I’d based the game’s location on Northern California! That last question in particular was so awesome, because it meant I’d really achieved my goal of representing the area well, and we chatted for a bit about the area we both once lived in.

I was also really happy with how portals worked in the end. I think they’re beautiful, and really capture the strange, liminal experience I wanted the game to have. It was more of a challenge than I was expecting, and it made me really learn so many of Unreal’s programming systems. It built my confidence so much, I’m programming with C++ now!

More than anything, the game accomplished what I’d wanted it to: it told an emotional journey that people genuinely connected with, and I became familiar with so many of Unreal’s systems. It was the exact project I needed to dive head-first into the engine’s tools. I learned how to use blueprints, materials, audio, UI widgets, its different tool modes, profiling and debugging tools… I went from nervously poking around the engine’s internals to being able to confidently utilize UE5, with an understanding of the gameplay framework and the interlocking systems within it.

What Got Cut

So much. I touched on it in what went wrong, but I felt like it’d be helpful to have a list of just how much I had to remove to make the finish line and make something that fit my themes. In full:

- Puzzles, entirely. I originally wanted the player to traverse through three separate times (past, present, future), where they’d have to use some kind of timelock item to make things appear in the other timelines. Portals would enable you to go through these times in different areas, and you would always travel through the times in the same order. I playtested some concepts like a locked room that you had to use time traversal and timelocks to find a way to get around the door. This idea got chopped up so many times until I ended up at the cassette system, which mostly used audio to lead players around the house, with little guesswork to be done.

- A separate, otherworld-like level area. I actually think this was something I could have implemented if the portals did not eat up my time, but I struggled so much to implement the version that actually teleported the player. Even though the teleportation worked, outside of the pressing framerate issue, I had gaps in my knowledge about concepts like level streaming.

- The original game mechanic, which was essentially pointing a spot light around and having objects appear when the light collided with it. This was one of the very first things I built for the game, and is what got removed for portals.

- Traversal mechanics. I originally wanted to have the player be able to navigate the game world with tools like clambering, jumping, sprinting—this was long before I’d settled on a much more somber tone. I was trying to avoid making a walking sim without realizing that walking sims were very useful for the exact type of story I was trying to tell.

- AI. There was a brief point where I’d discussed the idea of making the house feel haunted with my advisors. The idea was that you would actually be confronted by spirits to amplify the horror element.

Lessons Learned

I think the biggest lesson was that it is really hard to make a game on your own. I had to learn that my game ideas were unrealistic for the timeline and my skill level. Fundamentally, it was just humanly impossible for one person to make the entire original project I wanted to make in only 9 months.

- It’s important to always be aware of scope. It is natural to have endless dreams of new designs, but it is skillful to be able to recognize what can be done within the time remaining based on how many people are working on the project.

- Project management is just as important as making the project. I made the mistake of not using a task tracker, and relied on my own ability to manage myself too much. If you’re working solo, you have to give yourself deadlines, lists of what to do, and you have to check in on what’s been done and what needs doing. You can’t just say “I’ll get around to it”! You have to actually track and manage what you’re doing!

- If something isn’t working, sometimes it’s best to find a new solution. I held on to the render target version of the portals for too long, and sat stuck on the same problem for essentially weeks.

Technical Challenges

Here’s a brief, summarized overview of the technical challenges that I had to either solve or find new solutions for over the duration of the project.

- Render targets causing framerate drops: I ran into consistent performance issues using real-time render targets with Lumen and post-processing active. I believe this was in part due to the fact that I didn’t have anything set up to manage memory or garbage collect.

- Events triggering out of order: my dialogue system had issues with some later dialogue sections playing earlier than intended. It was built using mostly switch and if conditionals and some enums. The really critical error was storing the text directly in text boxes in blueprint instead of making use of data-driven design.

- Assets importing incorrectly: I wasn’t familiar with the Blender to Unreal asset pipeline, and had to learn how asset pipelines worked in general to be able to build a decent one for my artists.